Pericarditis: symptoms, diagnosis, treatment

Case presentation

A 55-year-old woman presents with chest pain. She reports the chest pain started several days ago and describes it as sharp and brief. When she sits up, the pain improves. She has no significant illnesses in her past medical history but endorses a viral respiratory infection a few days ago. On physical exam, she is in no acute distress. She has a low-grade fever. ECG shows widespread ST segment elevation and PR depression in the precordial leads.

Relevance

Pericarditis is the most common form of pericardial disease worldwide and is typically encountered in young and middle-aged people.

Main causes of acute pericarditis include:

| Categories | Causes | Frequency |

| A. Idiopathic | Unknown | Mostly frequent |

| B. Infectious causes: | ||

| Viral | Epstein-Barr, influenza, hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, mumps, echovirus, adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, varicella, rubella, human herpesvirus, parvovirus, coxsackie | Most frequent in developed countries |

| Bacterial | Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Coxiella burnetii, streptococcus, staphylococcus, pneumococcus, legionella, salmonella, haemophilus | Rare (with the exception of mycobacterium tuberculosis) |

| Fungal | Candida, aspergillosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis | Very rare |

| Parasitic | Toxoplasma, echinococcus | Very rare |

| C. Non-infectious causes: | ||

| Neoplastic | Primary: pericardial mesothelioma Secondary tumours: leukaemia, breast cancer, lung cancer, lymphoma, melanoma | Frequent as secondary metastasis |

| Metabolic | Hypothyroidism, renal failure, hypercholesterolaemia, gout, anorexia nervosa | Frequent |

| Cardiovascular | Acute myocardial infarction, Dressler’s syndrome, aortic dissection | Frequent |

| Autoimmune | Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren syndrome, dermatomyositis, sarcoidosis, systemic vasculitis’s, Behçet’s syndrome, familial Mediterranean fever | Frequent |

| Traumatic and iatrogenic | Catheterisation, surgery, chest trauma, radiation | Frequent |

| Drug-related | Phenytoin, minoxidil, isoniazid, procainamide, hydralazine, methyldopa, doxorubicin, amiodarone, clozapine, streptomycin | Rare |

| Other | Congenital absence of pericardium | Rare |

Aetiology depends on the type of pericarditis:

| Serous pericarditis | Autoimmune disease | Systemic lupus erythematosus, Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Uraemia | ||

| Viral illness | Coxsackie virus | |

| Fibrinous pericarditis | Complication of myocardial infarction | 1-3 days and several weeks after (Dressler syndrome) |

| Uraemia | ||

| Rheumatic fever | ||

| Haemorrhagic | Tuberculosis | |

| Malignancy | ||

| Constrictive | Radiation therapy | |

| Open heart surgery | ||

| Viral illness | ||

| Tuberculosis |

Pathogenesis of the disease

- inflammation of the pericardium can cause chest pain;

- movement of the heart can cause friction between the 2 pericardial layers, producing a friction rub;

- inflammation may cause a pericardial effusion.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is clinical and can be made based on two of the following criteria:

Clinical Findings:

- Chest pain (>85% to 90% of cases) that usually radiates to the trapezius ridge of the left shoulder or arm and resembles ischaemic pain. However, retrosternal pain in acute pericarditis is mainly sharp and pleuritic, which augments in the supine position with cough and deep inspiration. Conversely, it usually subsides in the upright position and by leaning forward due to decrease of the pressure on the parietal pericardium:

- sharp pleuritic chest pain that is worsened by inhalation;

- pain is also relieved by sitting up and leaning forward;

- shoulder pain (referred pain) (pericarditis is innervated by phrenic nerve).

Physical exam

- May have a fever.

- Friction rub (pathognomonic) – Auscultation exposes a pericardial friction rub (pathognomonic sign for pericarditis) is best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the left sternal border, with the patient leaning forward. The auscultation of pericardial friction rub is highly specific for acute pericarditis (specificity approximately 100%).

- Kussmaul sign (seen in constrictive pericarditis).

- ↑ jugular venous distention on inspiration.

- Hypotension, tachycardia, pulsus paradoxus, and impaired diastolic filling in constrictive pericarditis.

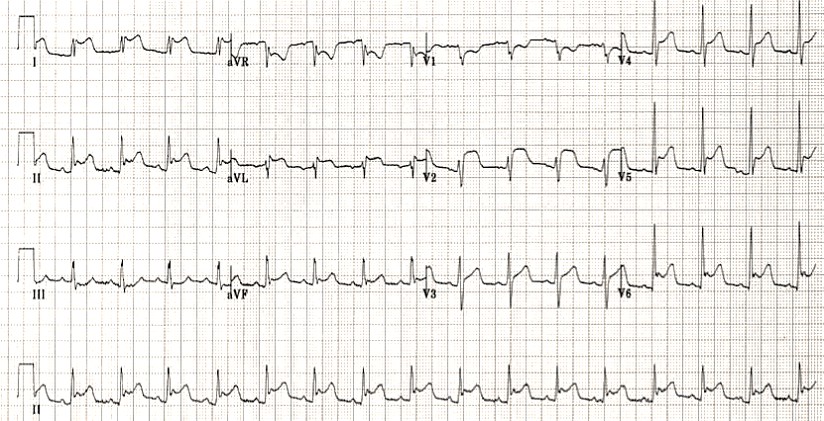

ECG Findings

- the occurrence of ST-elevation less than 5 mm;

- ST-segment concavity;

- widespread ST segment elevation;

- more extensive lead involvement;

- less prominent reciprocal ST-segment depression;

- PR segment depression, especially in lead II and in all leads except aVR;

- PR-segment elevation in aVR, with reciprocal PR-segment depression in other leads;

- the absence of abnormal Q-waves;

- variability in the time of T-wave inversion occurrence following ST-segment elevation;

- the lack of QRS widening and QT interval shortening in leads with ST elevation;

- upright T waves;

- weeks after pericarditis, this will become inverted T waves.

NB! classic ECG signs may be absent in uremic pericarditis

Laboratory Tests

Elevation of inflammatory markers is common in patients presenting with acute pericarditis such as:

- white blood cells (WBCs) count;

- ↑ erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR);

- ↑ C-reactive protein (CRP);

- may have ↑ troponin I, T, creatine phosphokinase.

* The evaluation of troponins does not seem to exhibit prognostic value on acute pericarditis.

* Interestingly, pericarditis patients with elevated biomarkers of myocardial injury almost always exhibit ECG changes characteristic of ST-segment elevation.

The prognostic role is promising for carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1), which is an immune inhibitory protein, and for MHC class I chain related protein A (MICA), which exhibits an immune stimulating function in patients with acute and recurrent pericarditis. CEACAM1 and MICA are serum proteins that can be released from damaged or inflamed tissues in patients with pericarditis are found to be increased as well.

A routine laboratory evaluation should include markers of renal function (urea, creatinine), electrolytes, LDH and transaminases (SGOT, SGPT). If there is a clinical indication, more specific tests may be ordered, such as blood cultures, thyroid function hormones, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA), anti-extractable nuclear antigens (ENA), HIV testing and even pericardial biopsy.

Chest X-ray

Usually within normal limits since an increased cardiothoracic index is exhibited when pericardial effusion is more than 300 ml. Signs of pleuropericardial involvement may be found in the background of pleuropulmonary disease in the chest X-rays of patients with acute pericarditis. Chest X-rays may reveal malignancies, sarcoidosis, or several infections, which may be the cause of acute pericarditis.

N.B.! A patient presenting with new and otherwise unexplained cardiomegaly, especially in the setting of clear lung fields, should be evaluated for acute pericarditis

Imaging

| Imaging | indication |

| Transthoracic Echocardiography | to assess for pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade |

| Radiography | To rule out pneumonia or other pulmonary pathology. Constrictive pericarditis may have pericardial calcifications on radiography |

Echocardiography

Pericardial effusion, either new appearing or worsening, is typically mild and is evident in 60% of cases. Pericardial effusion, based on the size at diastole, is characterised as mild (<10 mm), moderate (10-20 mm), or large (>20 mm). The hallmark of benign, idiopathic effusion is a clear ECHO-free space, whereas malignancy, bacterial infection, and haemorrhagic effusions are more likely to have solid components or stranding.

CT/CMR

Cardiac CT aids in the assessment of pericardial calcifications and thickening and the evaluation of concomitant diseases. CMR can provide the characterisation of cardiac tissue, the assessment of thickening and constriction, and the evaluation of myocardial involvement. CMR does not require radiation or nephrotoxic contrast agents. Furthermore, baseline late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) seen on CMR may correlate with inflammation severity. These techniques demonstrate pericardial thickening (>5 mm). This technique also has several weaknesses as it is time-consuming, high cost, not widely available, and requires stable patients and rhythms. In addition, patients with severe renal impairment and pacemakers may not be eligible candidates.

The following groups of patients seem most likely to benefit from cardiac MRI imaging for pericarditis:

- Patients with persistent chest pain after a negative ischemic evaluation.

- Patients with non-ischemic chest pain suspicious for pericarditis, but no detectable effusion on 2-D echocardiography.

- Patients with non-ischemic chest pain suspicious for pericarditis, but a poor quality or non-diagnostic 2-D echo study.

- Patients with recurrent chest pain after a negative ischemic evaluation and a negative “non-cardiac” chest pain evaluation.

- Younger patients with atypical chest discomfort and a low likelihood of coronary atherosclerotic disease.

Nuclear medicine

In selected cases, positron emission tomography (PET) alone, or preferably in combination with CT (PET/CT), can be indicated to depict the metabolic activity of pericardial disease. Pericardial uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) tracer in patients with solid cancers and lymphoma is indicative of (malignant) pericardial involvement, thus providing essential information on the diagnosis, staging and assessment of the therapeutic response.

Cardiac catheterization

This demonstrates elevation and equalization of filling pressures. In the typical case, the difference in filling pressures between the right ventricle and left ventricle does not exceed 6 mmHg. The right atrial waveform shows rapid ‘x’ and ‘y’ descents, and the mean pressure does not decrease normally with inspiration or may show Kussmauls sign.

According to the 2015 ESC guidelines on pericardial disease, the definite diagnosis of viral pericarditis derives from the comprehensive workup of histological, cytological, immunobiological and molecular investigations in pericardial fluid and pericardial/epicardial biopsies; otherwise, the term ‘presumed viral pericarditis’ should be used.

For the diagnosis of purulent pericarditis, urgent pericardiocentesis is recommended and pericardial fluid should be sent for bacterial, fungal and tuberculous studies. Blood should be drawn for cultures.

Furthermore, urgent TTE or CT is recommended in patients with a history of chest trauma and systemic arterial hypotension. Lastly, as far as malignancies are concerned, cytological analyses of pericardial fluid are recommended.

Main analyses to be performed on pericardial fluid:

| Analysis | Test |

| General chemistry | Protein level >3g/dL, protein fluid/serum ration >0,5, lactate dehydrogenase >200IU/L, fluid/serum ratio >0.6, blood cell count. |

| Cytology | Cytology (higher volumes of fluid, centrifugation, and rapid analysis improve diagnostic yield). |

| Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | PCR for tuberculosis |

| Microbiology | Mycobacterium cultures, aerobic and anaerobic cultures. |

Definitions and diagnostic criteria for pericarditis

| Pericarditis | Definition and diagnostic criteria |

| Acute | Inflammatory pericardial syndrome to be diagnosed with at least 2 of the 4 following criteria: (1) pericarditic chest pain (2) pericardial rubs (3) new widespread ST-elevation or PR depression on ECG (4) pericardial effusion (new or worsening) Additional supporting findings: – Elevation of markers of inflammation (i.e. C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and white blood cell count); – Evidence of pericardial inflammation by an imaging technique (CT, CMR). |

| Incessant | Pericarditis lasting for >4-6 weeks but <3 months without remission. |

| Recurrent | Recurrence of pericarditis after a documented first episode of acute pericarditis and a symptom-free interval of 4-6 weeks or longer. |

| Chronic | Pericarditis lasting for >3 months. |

Differential diagnosis

| Disease | Distinguishing factor |

| Cardiac tamponade | pulsus paradoxus and Beck triad on exam |

| Myocardial infarction | more focal ST elevation on ECG suggestive of anatomic damage |

Major differential diagnoses include acute coronary syndromes with ST-segment elevation and early repolarization.

Diagnosis formulation

I. Etiological characteristics.

- Pericarditis in bacterial infections I32.0.

- Pericarditis in infectious and parasitic diseases I32.1.

- Pericarditis in other diseases I32.8.

- Pericarditis unspecified I32.9.

II. Pathogenetic and morphological variants.

- Chronic adhesive I31.0.

- Chronic constrictive I31.1, including pericardial calcification.

- Hemopericardium I31.2.

- Pericardial effusion (non-inflammatory) – hydropericardium I31.3, including chylopericardium.

III. Complication.

- Myopericarditis.

- Perimyocarditis.

IV. The character of the flow.

- Acute.

- Subacute.

- Chronic.

- Recurrent.

V. Assessment of the severity of pericardial effusion according to ultrasound (ultrasound) and other research methods (minor, moderate, significant).

VI. CH (0-III stage, I-IV FC).

Tactics

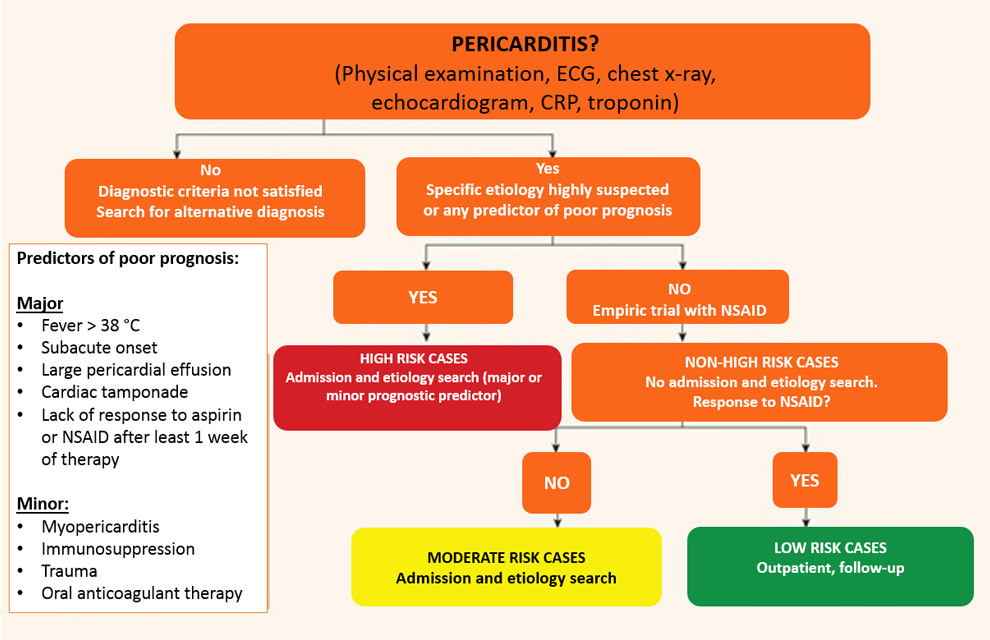

It is not mandatory to search for the aetiology in all patients, especially in countries with a low prevalence of TB, because of the relatively benign course associated with the common causes of pericarditis and the relatively low yield of diagnostic investigations.

The major risk factors associated with poor prognosis after multivariate analysis include:

- high fever [>38°C (>100.4°F)]

- subacute course (symptoms over several days without a clear-cut acute onset)

- evidence of large pericardial effusion (i.e. diastolic echo-free space >20 mm), cardiac tamponade and failure to respond within 7 days to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Other risk factors should also be considered (i.e. ‘minor risk factors’); these are based on expert opinion and literature review, including pericarditis associated with myocarditis (myopericarditis), immunodepression, trauma and oral anticoagulant therapy.

On this basis a triage for acute pericarditis is proposed. Any clinical presentation that may suggest an underlying aetiology (e.g. a systemic inflammatory disease) or with at least one predictor of poor prognosis (major or minor risk factors) warrants hospital admission and an aetiology search.

In the management of pericardial syndromes, a major controversy is the role of an extensive aetiological search and admission for all patients with pericarditis or pericardial effusion.

On this basis, auscultation, ECG, echocardiography, chest X-ray, routine blood tests, including markers of inflammation (i.e., CRP and/or ESR) and myocardial lesions (CK, troponins), are recommended in all cases of suspected pericarditis.

The major specific causes to be ruled out are bacterial pericarditis (especially TB), neoplastic pericarditis and pericarditis associated with a systemic disease (generally an autoimmune disease).

Next, an assessment of risk factors (major or minor) is carried out.

CT and/or CMR are recommended as second-level testing for diagnostic workup in pericarditis.

Diagnostic tests of the first and second levels at suspicion of pericarditis

| Level | Investigation |

| 1 st level (all cases) | Markers of inflammation (i.e. ESR, CRP, white blood cell count). Renal function and liver tests, thyroid function. Markers of myocardial lesion (i.e. troponins, CK). ECG Echocardiography Chest X-ray |

| 2nd level (if 1st level not sufficient for diagnostic purposes) | CT and/or CMR Analysis of pericardial fluid from pericardiocentesis, or surgical drainage, for cardiac tamponade or suspected bacterial, neoplastic pericarditis, or symptomatic moderate to large effusions not responding to conventional anti-inflammatory therapy. Additional testing should be directed to specific aetiologies according to clinical presentation (presence of high risk clinical criteria). |

Treatment

Patients identified with a cause other than viral infection, specific therapy appropriate to the underlying disorder is indicated.

The first non-pharmacological recommendation is to restrict physical activity beyond ordinary sedentary life until resolution of symptoms and normalization of CRP for patients not involved in competitive sports. Athletes are recommended to return to competitive sports only after symptoms have resolved and diagnostic tests (i.e. CRP, ECG and echocardiogram) have been normalized. A minimal restriction of 3 months (after the initial onset of the attack) has been arbitrarily defined according to expert consensus.

Aspirin or NSAIDs are mainstays of therapy for acute pericarditis.

| Drug | Usual dosing | Tx duration | Tapering |

| Aspirin | 750-1000 mg every 8h | 1-2 weeks | Decrease doses by 250-500 mg every 1-2 weeks |

| Ibuprofen | 600 mg every 8h | 1-2 weeks | Decrease doses by 200-400 mg every 1-2 weeks |

| Colchicine | 0.5 mg once (<70 kg) or 0.5 mg b.i.d. (≥70 kg) | 3 months | Not mandatory, alternatively 0.5 mg every other day (<70 kg) or 0.5 mg once (≥70 kg) in the last weeks |

The choice of drug should be based on the history of the patient (contraindications, previous efficacy or side effects), the presence of concomitant diseases (favouring aspirin over other NSAIDs when aspirin is already needed as antiplatelet treatment) and physician expertise.

Colchicine is recommended at low, weight-adjusted doses to improve the response to medical therapy and prevent recurrences. Tapering of colchicine is not mandatory but may be considered to prevent persistence of symptoms and recurrence.

| Nonoperative | Indications |

| • Observation and treatment of the underlying cause | In cases of asymptomatic or small pericardial effusion Medical treatment: • NSAIDS for viral pericarditis • steroids and immunosuppressants for SLE, avoid immediately following MI to protect from ventricular wall rupture • dialysis for uremia • aspirin for post-MI pericarditis |

| • Pericardiocentesis | Required for large effusions and cardiac tamponade |

| Operative | Pericardiectomy reserved for recurrent disease |

Corticosteroids should be considered as a second option in patients with contraindications and failure of aspirin or NSAIDs because of the risk of favouring the chronic evolution of the disease and promoting drug dependence; in this case they are used with colchicine. If used, low to moderate doses (i.e. prednisone 0.2–0.5 mg/kg/day or equivalent) should be recommended instead of high doses (i.e. prednisone 1.0 mg/kg/day or equivalent). The initial dose should be maintained until resolution of symptoms and normalization of CRP, then tapering should be considered.

Recommendations for the treatment of acute pericarditis:

- Aspirin or NSAIDs are recommended as first-line therapy for acute pericarditis with gastroprotection.

- Colchicine is recommended as first-line therapy for acute pericarditis as an adjunct to aspirin/NSAID therapy.

- Serum CRP should be considered to guide the treatment length and assess the response to therapy.

- Low-dose corticosteroids should be considered for acute pericarditis in cases of contraindication/failure of aspirin/ NSAIDs and colchicine, and when an infectious cause has been excluded, or when there is a specific indication such as autoimmune disease.

- Exercise restriction should be considered for non-athletes with acute pericarditis until resolution of symptoms and normalization of CRP. ECG and echocardiogram.

- For athletes, the duration of exercise restriction should be considered until resolution of symptoms and normalization of CRP. ECG and echocardiogram—at least 3 months is recommended.

- Corticosteroids are not recommended as first-line therapy for acute pericarditis.

Recurrent pericarditis

Recurrent pericarditis therapy should be targeted at the underlying aetiology in patients with an identified cause. Aspirin or NSAIDs remain the mainstay of therapy. Colchicine is recommended on top of standard anti-inflammatory therapy, without a loading dose and using weight-adjusted doses (i.e. 0.5 mg once daily if body weight is <70 kg or 0.5 mg twice daily if it is ≥70 kg, for ≥6 months) in order to improve the response to medical therapy, improve remission rates and prevent recurrences.

In cases of incomplete response to aspirin/NSAIDs and colchicine, corticosteroids may be used, but they should be added at low to moderate doses to aspirin/NSAIDs and colchicine as triple therapy, not replace these drugs, in order to achieve better control of symptoms. Corticosteroids at low to moderate doses (i.e. prednisone 0.2–0.5 mg/kg/day) should be avoided if infections, particularly bacterial and TB, cannot be excluded and should be restricted to patients with specific indications (i.e. systemic inflammatory diseases, post-pericardiotomy syndromes, pregnancy) or NSAID contraindications (true allergy, recent peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal bleeding, oral anticoagulant therapy when the bleeding risk is considered high or unacceptable) or intolerance or persistent disease despite appropriate doses. Although corticosteroids provide rapid control of symptoms, they favour chronicity, more recurrences and side effects. If corticosteroids are used, their tapering should be particularly slow. A critical threshold for recurrences is a 10–15 mg/day dose of prednisone or equivalent. At this threshold, very slow decrements as small as 1.0–2.5 mg at intervals of 2–6 weeks are useful. In cases of recurrence, every effort should be made not to increase the dose or to reinstate corticosteroids. After obtaining a complete response, tapering should be done with a single class of drug at a time before colchicine is gradually discontinued (over several months in the most difficult cases). Recurrences are possible after discontinuation of each drug. Each tapering should be attempted only if symptoms are absent and CRP is normal.

| Drug | Usual initial dose | Tx duration | Tapering |

| Aspirin | 500-1000 mg every 8h (range 1.5-4 g/day) | weeks- months | Decrease doses by 250-500 mg every 1-2 weeks |

| Ibuprofen | 600 mg every 8h (range 1200-2400 mg) | weeks- months | Decrease doses by 200-400 mg every 1-2 weeks |

| Indomethacin | 25-50 mg every 8h: start at lower end of dosing range and titrate upward to avoid headache and dizziness | weeks- months | Decrease doses by 25 mg every 1-2 weeks |

| Colchicine | 0.5 mg twice or 0.5 mg daily for patients <70 kg or intolerant to higher doses | At least 6 months | Not necessary, alternatively 0.5 mg every other day (<70 kg) or 0.5 mg once (≥70 kg) in the last weeks |

Drugs such as IVIG, anakinra and azathioprine may be considered in cases of proven infection-negative, corticosteroid-dependent, recurrent pericarditis not responsive to colchicine after careful assessment of the costs, risks and eventually consultation by multidisciplinary experts, including immunologists and/or rheumatologists, in the absence of a specific expertise.

As a last resort, pericardiectomy may be considered, but only after a thorough trial of unsuccessful medical therapy, and with referral of the patient to a centre with specific expertise in this surgery.

Prednisolone reduction regimen:

| Starting dose 0.25-0.50 mg/kg/day | Tapering |

| >50 mg | 10 mg/day every 1-2 weeks |

| 50-25 mg | 5-10 mg/day every 1-2 weeks |

| 25-15 mg | 2.5 mg/day every 2-4 weeks |

| <15 mg | 1.25-2.5 mg/day every 2-4 weeks |

Avoid higher doses except for special cases, and only for a few days, with rapid tapering to 25 mg/day. Prednisone 25 mg are equivalent to methylprednisolone 20 mg.

Every decrease in prednisone dose should be done only if the patient is asymptomatic and C-reactive protein is normal, particularly for doses <25 mg/day.

Calcium intake (supplement plus oral intake) 1,200–1,500 mg/day and vitamin D supplementation 800–1000 IU/day should be offered to all patients receiving glucocorticoids. Moreover, bisphosphonates are recommended to prevent bone loss in all men ≥50 years and postmenopausal women in whom long-term treatment with glucocorticoids is initiated at a dose ≥5.0–7.5 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent.

Pericardiocentesis or surgical drainage are indicated for cardiac tamponade or suspected bacterial and neoplastic pericarditis.

Algorithm for the treatment of acute and recurrent pericarditis

Low-dose corticosteroids arc considered when there arc contraindications to other drugs or when there is an incomplete response to aspirin/NSAIDs plus colchicine; in this case physicians should consider adding these drugs instead of replacing other anti-inflammatory therapies.

Azathioprine is steroid-sparing and has a slow onset of action compared with IVIG and anakinra. Co« considerations may apply considering the cheaper solution first (e.g. aaathiophne) and resorting to more expensive options (e g. IVIG and anakinra) for refractory cases.

Complications

- Pericardial effusion and tamponade.

Prognosis

- Can be acute or chronic and may recur.

- Viral pericarditis is usually self-limited.

Most patients with acute pericarditis (generally those with presumed viral or idiopathic pericarditis) have a good long-term prognosis. Cardiac tamponade rarely occurs in patients with acute idiopathic pericarditis, and is more common in patients with a specific underlying aetiology such as malignancy, TB or purulent pericarditis. Constrictive pericarditis may occur in <1% of patients with acute idiopathic pericarditis, and is also more common in patients with a specific aetiology. The risk of developing constriction can be classified as low (<1%) for idiopathic and presumed viral pericarditis; intermediate (2–5%) for autoimmune, immune-mediated and neoplastic aetiologies; and high (20–30%) for bacterial aetiologies, especially with TB and purulent pericarditis. Approximately 15–30% of patients with idiopathic acute pericarditis who are not treated with colchicine will develop either recurrent or incessant disease, while colchicine may halve the recurrence rate.

This article is for informational purposes only. Self-medication can be harmful to your health. The use of any drugs mentioned in this article is possible only as directed and under the supervision of a physician.

Literature:

1. Klein A. L., Abbara S., Agler D. A., Appleton C. P., Asher C. R., Hoit B., Hung J., Garcia M. J., Kronzon I., Oh J. K., Rodriguez E. R., Schaff H. V., Schoenhagen P., Tan C. D., & White R. D. American Society of Echocardiography clinical recommendations for multimodality cardiovascular imaging of patients with pericardial disease: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr, 2013, Sept 26. (9): 965-1012.e15.

2. Markel G., Imazio M., Koren-Morag N., Galore-Haskel G., Schachter J., Besser M., Cumetti D., Maestroni S., Altman A., Shoenfeld Y., Brucato A., & Adler Y. CEACAM1 and MICA as novel serum biomarkers in patients with acute and recurrent pericarditis. Oncotarget, 2016 April 5. 7 (14): 17885-95.

3. Imazio M., Brucato A., Badano L., Charron P., & Adler Y. What’s new in 2015 ESC guidelines on pericardial diseases? J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown), 2016, May 17. (5): 315-22.

4. J. Ronald Mikolich. New Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Pericarditis: A Cardiac MRI Perspective Nov 05, 2015, , MD, FACC. Expert Analysis

5. Yehuda Adler, Philippe Charron, Massimo Imazio, Luigi Badano, Gonzalo Barón-Esquivias, Jan Bogaert, Antonio Brucato, Pascal Gueret, Karin Klingel, Christos Lionis, Bernhard Maisch, Bongani Mayosi, Alain Pavie, Arsen D Ristić, Manel Sabaté Tenas, Petar Seferovic, Karl Swedberg, Witold Tomkowski, ESC Scientific Document Group, 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), European Heart Journal, Volume 36, Issue 42, 7 November 2015, Pages 2921-2964, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318

Register on our website right now to have access to more learning materials!

ClinCaseQuest Featured in SchoolAndCollegeListings Directory

Exciting News Alert! We are thrilled to announce that ClinCaseQuest has been successfully added to…

We presented our experience at AMEE 2023

AMEE 2023 took place from 26-30 August 2023 at the Scottish Event Campus (SEC), Glasgow,…

We are on HealthySimulation – world’s premier Healthcare Simulation resource website

We are thrilled to announce that our Simulation Training Platform “ClinCaseQuest” has been featured on…

Baseline Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Cancer Patients Scheduled to Receive Cardiotoxic Cancer Therapies (Anthracycline Chemotherapy) – Online Calculator

Baseline cardiovascular risk assessment in cancer patients scheduled to receive cardiotoxic cancer therapies (Anthracycline Chemotherapy)…

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) – Online calculator

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a scale designed to assess the…

SESAM 2023 Annual Conference

We are at SESAM 2023 with oral presentation “Stage Debriefing in Simulation Training in Medical…